ON OUR OWN TERMS: Blood and guts and memory at the Baltimore Museum of Art, by Shaawan Francis Keahna

When I finally figure this whole Zoom thing out and Sky Hopinka’s face fills my too-big flat screen monitor, I think about Dislocation Blues. I am often thinking about Dislocation Blues. It animates my life in ways I’m sure my children will comprehend better than I ever will. My children haven’t been born yet. They are an idea, yet they infect—yes, infect—the incoherent toil of my daily life already.

This is going somewhere, I promise.

Sky’s guest curatorial venture, Don’t wait for me, just tell me where you’re going, is currently on display at the Baltimore Museum of Art as part of their dynamic program, Preoccupied: Indigenizing the Museum. Sky’s brought us a handful of experimental short films by Native American and Indigenous filmmakers he works with through the COUSIN collective, which began as a group of prolific Native people pushing the boundaries of film and narrative, since myceliating into a funder, producer, and cultural touchstone in its own right. It’s weird, watching a “they” become an “it.” Just like it’s weird seeing Sky pop up, blinking at me, waiting for me to ask the questions. There are cycles we are beholden to. Worlds inside of worlds.

If you go to the page the BMA’s website has for Don’t wait for me, just tell me where you’re going, you might be lulled into a false sense of pleasant anticipation. The installation images show bucolic shots of beadwork, flowers, trees, and the edge of a mural—Indians, brown and scantily clad, leaning into each other with their eyes closed. There are these beautiful, gentle things I understand white and nonnative people to expect from us. A romanticized facade of Indigeneity, tempered by nature and our own perpetual death. This is no shade to the BMA—I know the utility of these images. I know marketing is a kind of seduction. When we seduce someone, we don’t really want them to see the thorns. When I name this aspect of the site, what I mean to do is give you context for everything this program really represents. The message I, a half-remembered ghost, took from these pieces in their totality.

When Sky appears on the screen, looking like a real adult, I remember eight years back. His shadow in the corner of our Skype call as he set up the camera rig to capture my own young face on a tiny screen, telling a story for a crowd I didn’t realize would come. For a split second, I imagine recording him on my enormous monitor, self-referential as it would be, and I smile.

Shaawan:

What common thread, what commonality, what story were you trying to tell with these projects coming through and being laid out in this way? Were you even trying to tell a larger story?

Sky:

It’s a broad story. It’s not so much driven by the formal aspects of these works, because they’re all very different—and I like that about them. Each of them together stakes its own position in this larger configuration of asking: how do they relate to ancestral memory? How do they relate to this idea in the future? But then, also, how are they grounded very much in their own respective presents?

Like with Lindsay’s work, you know, it’s filmed on sixteen millimeter. It’s very textural. Not only in terms of the images in her pieces, but just the brain of it, you know? There’s something—I want to say “archival,” but that risks fetishizing the use of sixteen millimeter—there’s something very apparent about the material. How that is related to suit the action of “All Around Junior Male” or the details of the beadwork. It gives a certain sense of life that runs counter to this idea of the “archive.”

Conversely, with Fox’s work, she’s doing things I haven’t seen anyone do before. She’s also created her own visual language. She’s guided through these different landscapes and these different ideas of colonial history. But she’s doing it very much on her terms, which I think is incredibly exciting, cinematically. Just how you experience it visually and how you can’t ignore it. Like you mentioned, the stills that they chose for the website don’t really betray the intensity of the work.

Some of the—I don’t want to say “aggressiveness,” but it’s certainly consistent with Miguel’s work, too, you know, it occupies its own different sense of place and space and history on its own terms. It feels unconcerned whether you can keep up, but it doesn’t do so in an antagonizing way, if that makes sense. That was something I was thinking about when titling the program and the note I had written for it. It’s inviting you along but it has its own pace. It makes space for your own pace as an audience member, whether you’re familiar with the work or experimental film or what these filmmakers are up to or not.

Shaawan:

What do you think is the intentionality and the consequence of us, the broader us, the pan-Indian us, telling our stories and making ourselves the subjects? What do you think the conversation is going to become, what do you think the conversation has been so far?

Sky:

I like that question a lot because I think it touches on, well. Even the direction, the idea of directionality in the title. Don’t tell me where you’re going, because this pendulum shifts back and forth all the time generationally in terms of the questions that we’re asking, the questions we’re asking now, making ourselves the subject of these works, or addressing ourselves in different ways. That’s going to be the thing that the next generation of filmmakers, artists, whoever react against, or respond to, whether conversationally, combatively. Even thinking about how twenty years ago, how much of what we have going on right now is in reaction to that.

There’s something that feels very contemporary with all of these works, even the sixteen millimeter stuff, it speaks to the way that these different artists can pull these older materials or older formats into the present and use them on their own terms, without feeling too beholden to what broader traditions might not suit them. What sort of new traditions are they creating? What certain practices are they creating? It is simultaneously concerned with the present, but it’s not disregarding the future.

I don’t know what the effect is or how it’s going to be, but I’m excited to find out. I’m excited to see what happens when I’m no longer part of the conversation and what other sort of voices are going to be picking it up or responding to what we’re doing right now.

Shaawan:

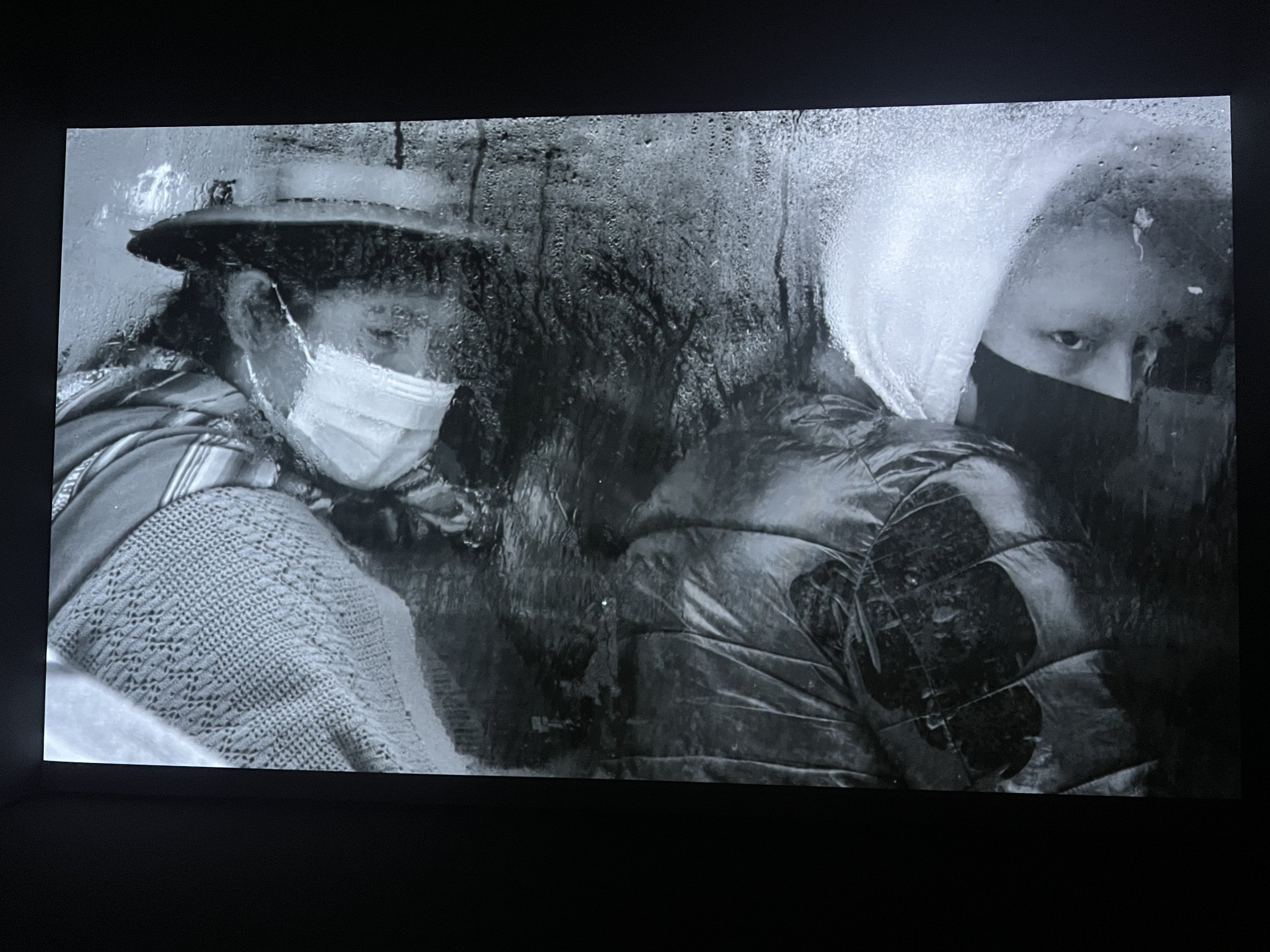

I want to return to that, “when I’m no longer part of the conversation,” because I think there’s something there. But for now, I’d like to ask about the cameras involved in these pieces. Miguel’s piece, for example, you think it’s still life, but then there’s this movement. Miguel’s is the most traditional in that it is very crisp, it is very clean. The other pieces are so textured, grainy, pixelated. So I’m wondering where you see Miguel’s piece fitting in this gradient you’ve created between the digital versus the fuzzy textural. Where does Miguel’s piece fit visually for you? Where does it land for you?

Sky:

Somewhere in the middle. I mean, not the middle of the program itself, but for your conversation: between the closeness of Lindsay’s work, the intimacy of it, whether it’s beadwork or athletes, to the literal distance that is being created in Miguel’s landscapes. It’s in conversance with Olivia and Woody’s piece, as well as Fox’s, where it’s about the movement to themselves, via the camera, via their edited approaches, and just the way they’re moving these images and layering them on top of each other.

There’s a certain pause or rest, if rest fits in Miguel’s piece, a certain quietness that I think offers a break to contemplate, to contend with the other works in different ways, especially how they liken to an afterimage, as it were. That’s really what I was using, or experiencing, with Miguel’s piece. I was processing. I needed time to process.

Shaawan:

With regards to Fox Maxy’s piece, do you see it as being almost the thesis of the loop, or are they all pretty much on a level playing field with each other? I understood this piece to be a very explicit refusal to the current moment of romanticized Indigeneity. Very explicitly refusing the role of the mystical Indian. I wondered if you elevated that piece to the same level I elevated it to, or if everything’s more even.

Sky:

I don’t think of them in a hierarchical sort of way. I think of them being conversant with each other. Whenever I do program, especially with films, I tend to think about how they exist together, how they create a dialogue together, complement each other or contradict each other or offer an experience that allows each film to breathe and exist on its own terms.

Experimental film is another way we can relate to time-based media or things we ingest over the course of the day. Fox’s work is pretty special, but so is Lindsay’s and Miguel’s and Olivia and Woody’s, and they’re all at very different stages in each of their careers. There’s something to that, too, where, again, how can this form a little experience as you move through time itself, watching these things? How does this affect your own view of what you’re seeing? Going from Fox’s to Miguel’s, how does that calm you down or rile you up?

Shaawan:

With Olivia Camfield and Woodrow Hunt’s film—if I have to play favorites, it was my favorite, because it took me by surprise. Film is an empathy machine, of course, and with all of these pieces I felt something different, but Camfield and Hunt’s moved me to tears very quickly, right at the end. They have their ancestor, you know, that little girl in the corner for the entire film. Even with all of the hot, model Natives posing with new Native fashion, they’re all modeling, they’re all being young and funny and hot and cute, and then there’s just this photograph of this ancestor. Watching over everything and being watched. Which brings me to the question I wanted to finish with, since we’re almost out of time.

You say blood is a gift and the past is a gift. How do you, as the curator, and then how do these films carry that gift?

Sky:

Say it again? I need to think about it. How do I as a curator and how do these films, these filmmakers, carry that gift?

Shaawan:

Yeah. How do you… how do you carry the gift of a past and the gift of your blood?

Sky:

There’s so many different ways. Through the practice. Through the questions. Through the mistakes. And, I guess, through all the things that come with—not only being a human, but just trying to figure it out. I think there’s something to trying and to the attempt that I think is how one carries that gift. That’s the thing I love about experimental film is that in the truest sense of the word, it’s an experiment. Some things are going to fail, some things are not going to be good, some things won’t land with an audience in the right way, some things are going to bring someone to tears. There always is that attempt—to try and connect in some way, visually, viscerally, auditorily. It’s about trying to be heard and trying to have something to say. Or even just trying to say nothing at all because you’re tired of having something to say!

It’s that movement, how things are never static, never stale, or maybe they should be stale sometimes! I think there’s value in boredom, there’s value in sitting somewhere and letting your mind wander. Try to account for that. What is blood? What is the land? What is this memory? We are all trying to explain that in different ways, in different languages.

I’m writing this from a film set in Baltimore, Maryland. We’re shooting something unusual, something experimental, though the set itself is blessedly regimented and carefully maintained by a good crew, a good team. As I polish this up, the FX artist is pulling silicone flesh from one of the actors. It’s eerily realistic—sheafs of skin falling to the chipped wooden table below with a loud, wet plop. I watch it curl in on itself. I think of the beheaded rattlesnake in Fox Maxy’s “Blood Materials,” undulant and pale as brown hands rend scaly flesh from the white meat beneath. I look down at the pilled, rug-like Tide Pod parody on my bright orange sweater, a Skyn Style hoodie I bought for sixty bucks at a powwow in Fort Belknap that says “Native Vibes.” I look at the vast, dark green expanse of Druid Hill Park and breathe the briny air slowly.

If I slow down, I can see my own little girl hovering in the corner, an afterimage. I couldn’t tell you if she’s past or future, only that she looks a lot like me. She’s always there, no matter whose land I walk on or what I’m doing. The path stretches out ahead, winding and unknowable.

I am trying. We all are.

Don’t wait for me, just tell me where you’re going will be at the Baltimore Museum of Art until December 1st. Admission is free.

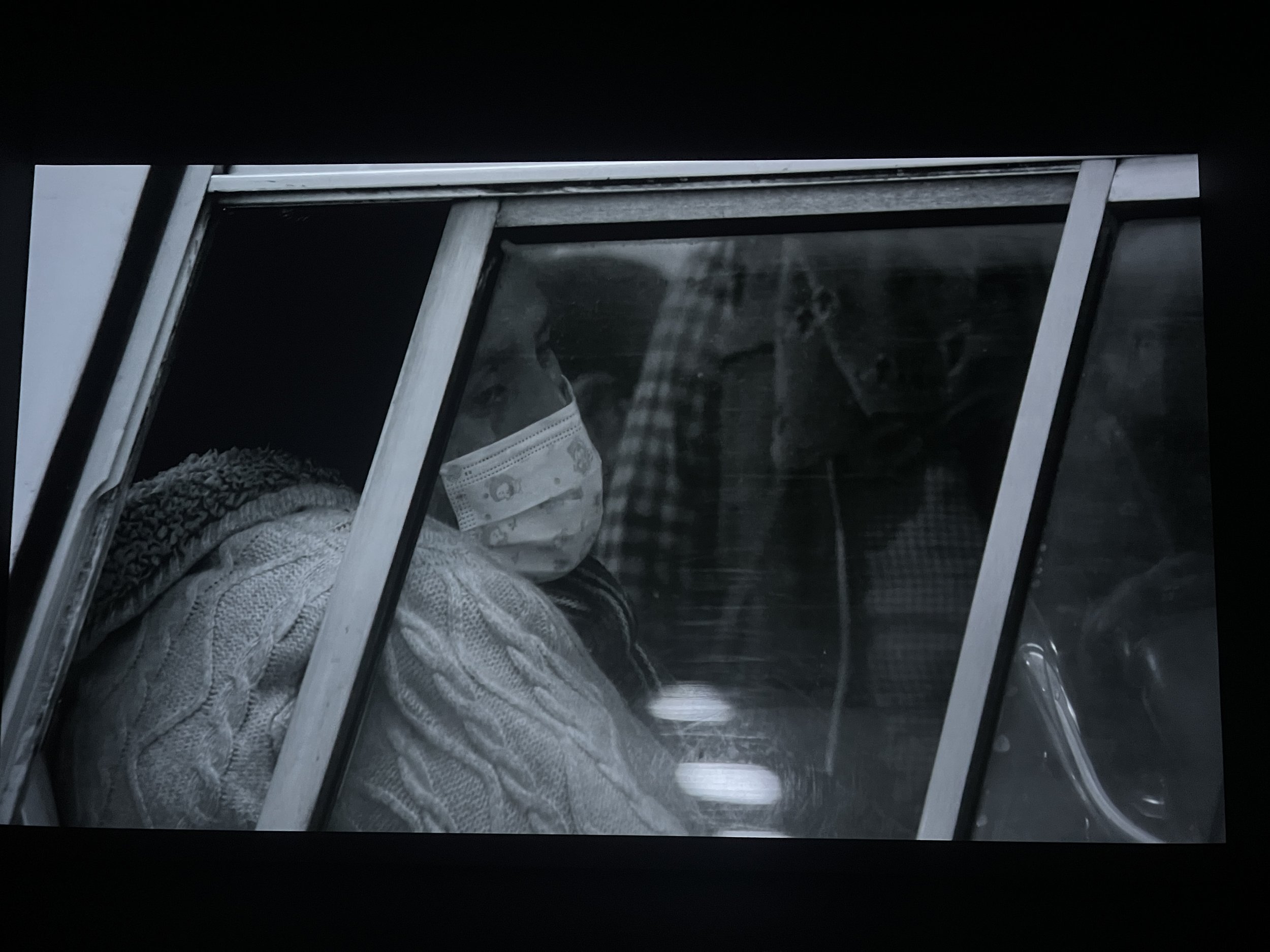

All Images from Cerro Saturno (2022) by Miguel Hilari (German/Aymara).